Hi all—Dan here! Today, we have a guest article for you from Alice Albrecht. Alice is one of the smartest and most experienced under-the-radar builders in AI today. She did a PhD in cognitive neuroscience at Yale and then spent 10 years in AI before becoming a founder. Today, she spends her time running re:collect, a startup building an AI-powered thought partner.

As part of her work at re:collect, she spends a lot of her time building software tools to enhance human creativity. She has an extensive knowledge of the research literature on what creativity is and how humans can do it better, and that’s exactly what she writes about for us in this article. It’s a detailed and actionable guide to the science of creativity and how to unlock it. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

Creativity is our greatest human asset. Beyond the personal joy of creative expression, creative thinking and problem-solving are key drivers of economic growth. Even though plenty of people may not think of themselves as “creatives,” everyone has the ability to think creatively. In that sense, it should be one of the great equalizers, especially as advances in AI and cheaper compute lower the bar for getting from a creative idea to a final output.

Even with the best tools available to turn our creative ideas into something more tangible, though, we still need to provide the initial seed of an idea and be able to judge whether we’re heading in the right direction. We’re still the creative directors of our own minds.

Given this innate capability, how can we improve our creative thinking? As a scientist and a builder, I’ve taken the approach of understanding “the system” and then looking at ways we can augment it. Understanding your own cognition makes it easier to change it.

The science of creativity

Creativity is the ability to produce an artifact or an idea that is both novel and useful given a particular social context (some definitions also include valuable as a necessary requirement). Novelty is an interesting concept if we take the position of, say, a child. In creativity research, it can mean that an idea has sprung from a connection that has never been made or is new to an individual but may be otherwise widely known.

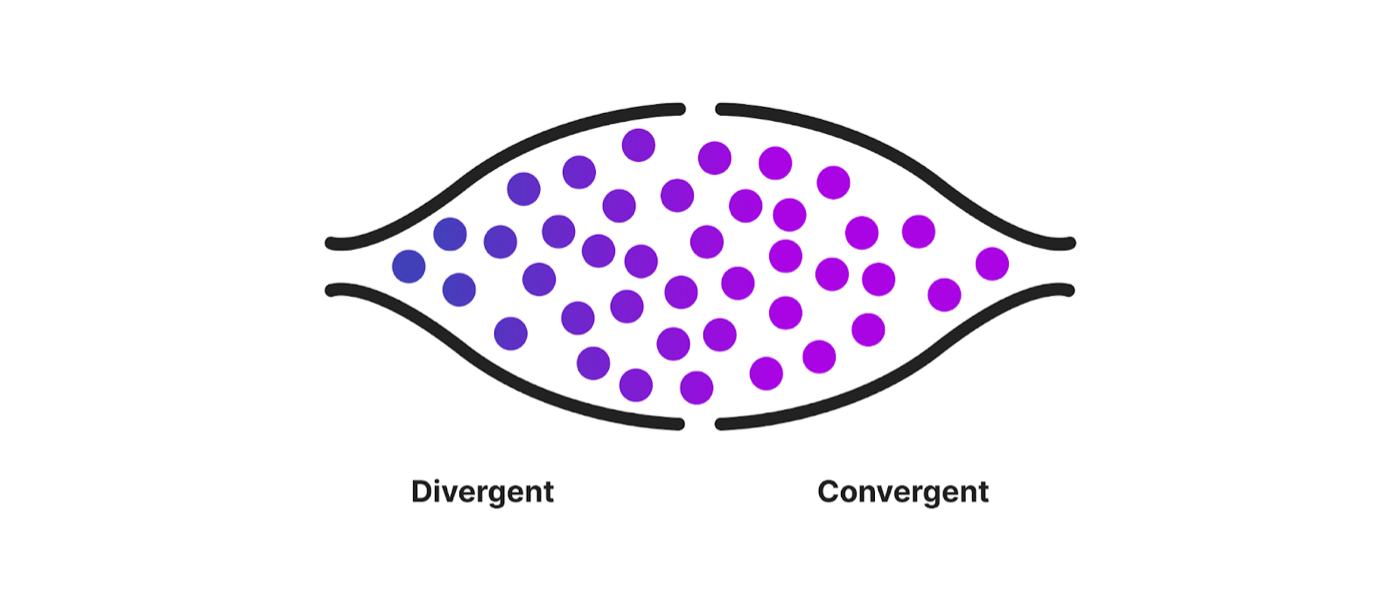

Researchers generally believe that creativity is a two-part process. The first is to generate candidate ideas and make novel connections between them, and the second is to narrow down to the most useful one. The generative step in this process is divergent thinking. It’s the ability to recall, associate, and combine a diverse set of information in novel ways to generate creative ideas. Convergent thinking takes into account goals and constraints to ensure that a given idea is useful. This part of the process typically follows divergent thinking and acts as a way to narrow in on a specific idea.

If you’ve been part of a “brainstorming” exercise, you’ve participated in this type of thinking. You may also have seen these concepts reframed as “flaring and focusing” or “explore vs. exploit.”

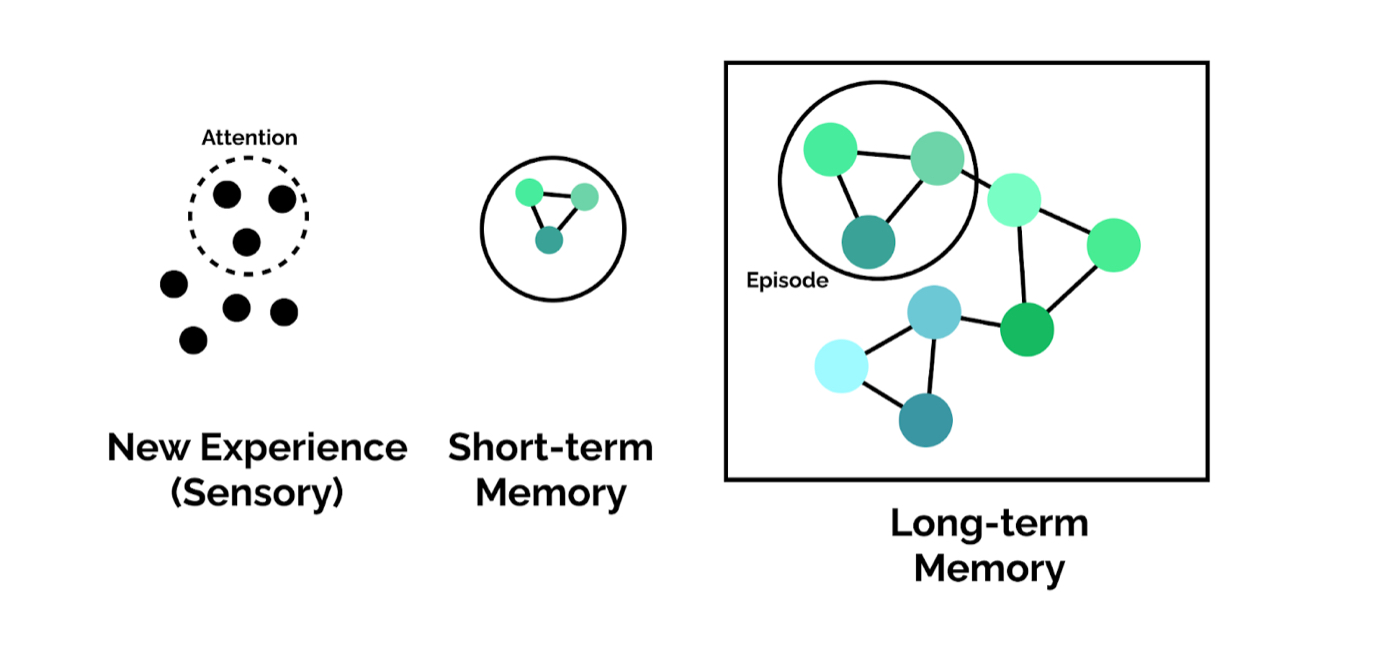

As our minds begin this dance between divergent and convergent thinking, we first need to have learned some information about how the world works and have some ideas to pull from. We can call our pile of ideas and experience knowledge. This makes memory a critical component of creativity. Memory is a complicated topic, but at a high level, as information related to language—or semantic information—and information related to your senses—or perceptual information—comes into our minds, it is encoded in episodes, or periods of time.As a memory moves from short-term to long-term storage, what’s represented in that memory is associated with existing memories (aka “schemas”), and your overall understanding of the world shifts slightly. If information is related to what you already know, attaching it to an existing part of your schema helps you understand that information more quickly because you’ve already seen something like it before. For instance, after you read this article, what you know about creativity will have changed. The way memories are associated makes it possible to connect your ideas later. In fact, recent evidence shows that semantic memory structure—how we relate language-based concepts—is one of the biggest predictors of creativity.

While we can study the output of our minds’ creative processes by measuring how well people do on different tests of creativity, understanding how our brains give rise to the creative experience helps us understand the process more deeply and fills in a critical component that is thus far missing—attention.Using neuroimaging techniques, scientists can peek into the black box of our brains and study what happens when someone is generating new ideas. For a moment, let’s assume we are such scientists. If we were to put our research participant (let’s call her Delilah) inside an fMRI scanner and ask her to come up with as many creative uses for a shoe while riding in a boat as she could in one minute, we would observe a volley of activity between specific brain networks.

When Delilah is coming up with all of these different uses (i.e., divergent thinking), a network of brain regions called the “default network” is activated. In brain imaging studies, this network shows the highest activation during spontaneous, self-generated thought—including mind wandering, which is specifically not related to a task. Delilah’s task doesn’t necessarily call for self-generated thought, given we’ve asked her to come up with these uses, but perhaps a stray thought about how hungry she is occurs to her, and now she’s thought of a way to use the shoe to catch fish.

Governing this process is a “control network” that allows us to think flexibly, inhibit outside distractions, and pull from our memory. The control network would help Delilah rule out using the shoe to walk down 5th Avenue, but by also engaging her attention, it could help keep the noise of the fMRI machine from distracting her. You can think of this network as supporting our convergent thinking, like a biological example of the adage, “Constraints breed creativity.”

Switching between the default and control networks is thought to be governed by a “salience network,” which helps us to engage each one effectively. Higher creative thinking scores are correlated with greater coupling between these networks. If Delilah comes up with a long and useful list of uses for that shoe, we should observe that she has a more integrated semantic memory structure that represents her knowledge and more dense connections between her default, control, and salience networks. Huzzah! Good work, Delilah.

Now that we have a high-level understanding of the components and the system underpinning creative thinking, we can start to unpack how we might affect our own creative systems for the better.

Build a good “memory bank” full of materials for creation

Memories are the materials needed for creative thinking. Consuming other people’s ideas in conversation by reading or listening to them (like you’re doing now!) stimulates creativity and deepens existing associations. To widen our divergent thinking funnel, we could try and seek out new ideas that are maximally different from our own, but this typically won’t work. It’s actually better to make incremental steps outside your own filter bubble because new information must overlap somewhat with what you already know to be effectively associated and assimilated. Read voraciously and engage deeply with a wide variety of content to build a richer memory bank for you to tap.

Click here to read the full post

Want the full text of all articles in RSS? Become a subscriber, or learn more.

Summary

- There’s no doubt that creativity is both a uniquely human skill and one of our greatest assets.

- But how do we make ourselves more creative?

- In this detailed and actionable guest post, re:collect’s Alice Albrecht lays out some of the science behind creativity and gives us some concrete ways to boost our own creative thinking, including:

- Building up a “memory bank” of materials for creation by reading widely and extensively, interacting with those materials, and creating the conditions for serendipity in our creative processes.

- Learning to recognize and tune our mental state, paying attention to when we’re too focused and when our minds are wandering.

- And getting muddy, making mistakes, and taking chances.